THE VOLUNTEER, December 2001 9

By James D. Fernández

H

ow much history, how much

sentiment, how much spirit, can

fit in a plain manila envelope?

When Jair Kessler, Associate

Director of NYU's Remarque Institute

for European Studies, recently learned

that the archives of the Abraham

Lincoln Brigade are now at the

Tamiment Library at NYU, she

recalled that her mother had left her a

set of letters that might be of interest

to the archive. It turns out that

Marjorie Polon--Jair's mother--as a

starry-eyed 14-year-old from New

York's upper west side, had somehow

become a pen pal--and purveyor of

fine tobacco--to a group of young

American volunteers who had gone to

fight fascism in the Spanish Civil War.

Though she rarely talked about this

episode in her life, Majorie had lov-

ingly saved the letters she received

from the boys on the front.

Jair and her sister inherited the

correspondence when their mother

died in 1977 and kept it until last

week. That's when Jair brought to

work a manila envelope labeled

"Marjorie -Spanish Civil War

Correspondence" and gave it to me,

asking me to donate the letters to the

Archives. I thanked Jair for the contri-

bution and chatted with her for a

while about her mom and the letters.

After Jair left my office, I thought I

would have another quick look at the

letters before walking the envelope

over to the library. I started reading,

and couldn't stop. Over the next day

and a half, instead of tending to the

urgent business of the imminent start

of a new academic year, I spent hours

carefully reading and transcribing the

letters, which had been written in

Spain between May and November of

1938. I don't know how to say this

without sounding trite, but I quickly

became consumed by the contents of

that manila envelope, drawn into its

world of history, sentiment and spirit.

A remarkably compelling cast of

characters emerges from this time cap-

sule. For starters, there's Harry

Hakam, apparently Marjorie's initial

contact in the Brigade. When I first

read Hakam's letters, I was tempted to

say that he writes like a Bogart imper-

sonator; it would probably be more

accurate--and less of an anachro-

nism--to suggest that Bogart and his

scriptwriters must have modeled the

actor's screen persona on men like

Hakam.

In any case, for some reason,

Hakam sent the young girl a list of 10

fellow brigadistas, suggesting that she

write to them: "Here you are, kid, 10

swell guys: they come no better. Send

them smokes and a photo. Tell them

funny stories and don't call them heroes.

A cigarette always was the best way of

starting a conversation and a correspon-

dence as well, so hop to it."

In this same note, next to each

comrade's name, Hakam offered a

cryptic thumbnail sketch: "Nat

Grossa ladies man and how; David

Drummond--a real guy; Joe

Biancatough but tender; Jerome

Ferroggiana--the long of it; George

Kaye--Hollywood's contribution;

Mike Pappasthe Greeks got a word

for him; Larry LusgartenEast Side;

Aaron Loppoffcall your chicks; Larry

Gayle--from director to first aid man;

Harry Hurst--a walking corpse."

In subsequent letters, Hakam is

often Bogart-gruff, telling the young

Marjorie not only whom she should

write to, but also what she should

write about. "Received your letter and

I don't like the poetry you wrote. I

would appreciate it much more if you

told me all about your love life, or

something about some dizzy dame in

your circles. What does your Maw

and Paw think of communists, espe-

cially those who go to Spain to fight

fascists? Is the rest of your brothers or

sisters (if any) on our side, or do you

live in a house divided as my family

is?" Hakam tells Marjorie that it's OK

with him for her to write to a Spanish

comrade. He also lets her know that

he'd like to receive a letter from one of

Marjorie's friends about whom she

had spoken in a letter: "Almost sounds

interesting enough to make me want to

meet the dame. So let her write, Marg,

for I got enough saved up in me to love

you both and then some."

In another letter, we see Hakam

trying to steer his young pen pal in an

attempt to improve his own standing

among his comrades: "My big friend

William (Mike) Bailey is kind of mad

because you sent his rival George

Kaye a letter and none to him. You

want to be careful because Mike is the

biggest guy in the battalion and

George is the shrimp. Anyway,

[Bailey] is my favorite over George so

I wish you would get busy and your-

self and a bunch of your pretty friends

to write to him. Don't forget to enclose

a few pictures and some cigarettes in

the same letter."

Marjorie's letters and their enclo-

sures--particularly photographs and

tobacco--obviously made the rounds

on the front lines. "In this part of the

Ten Swell Guys

and One Classy Dame

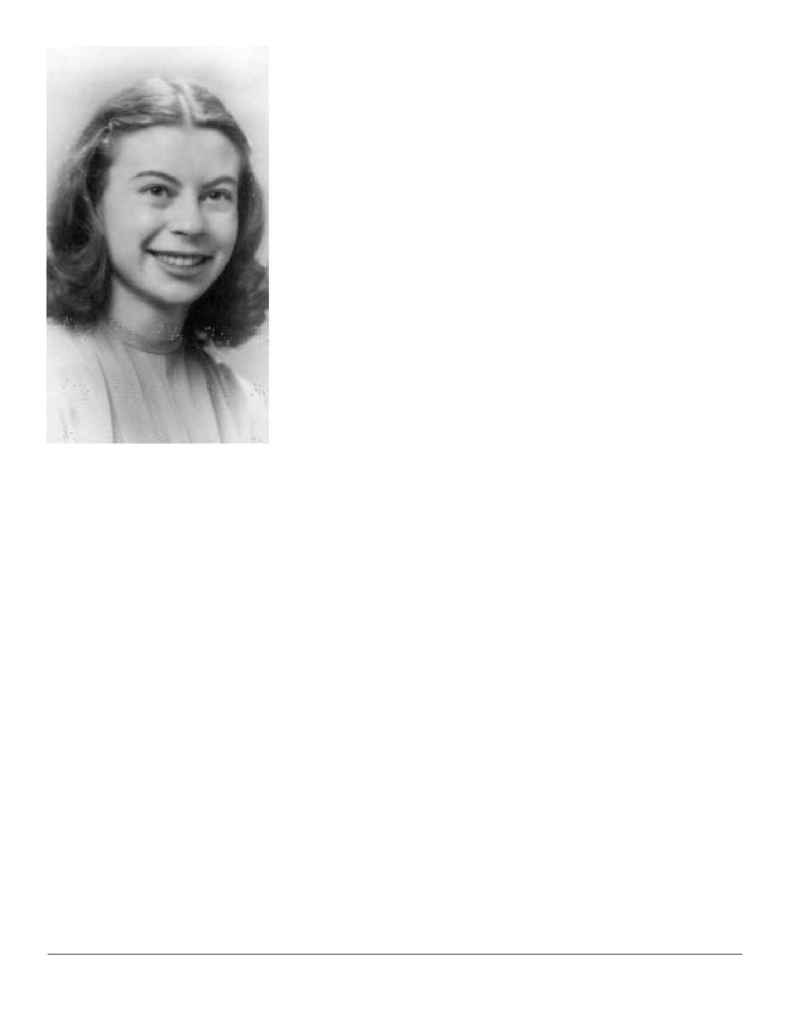

Marjorie Polon