278

Walton, Maio, and Hill

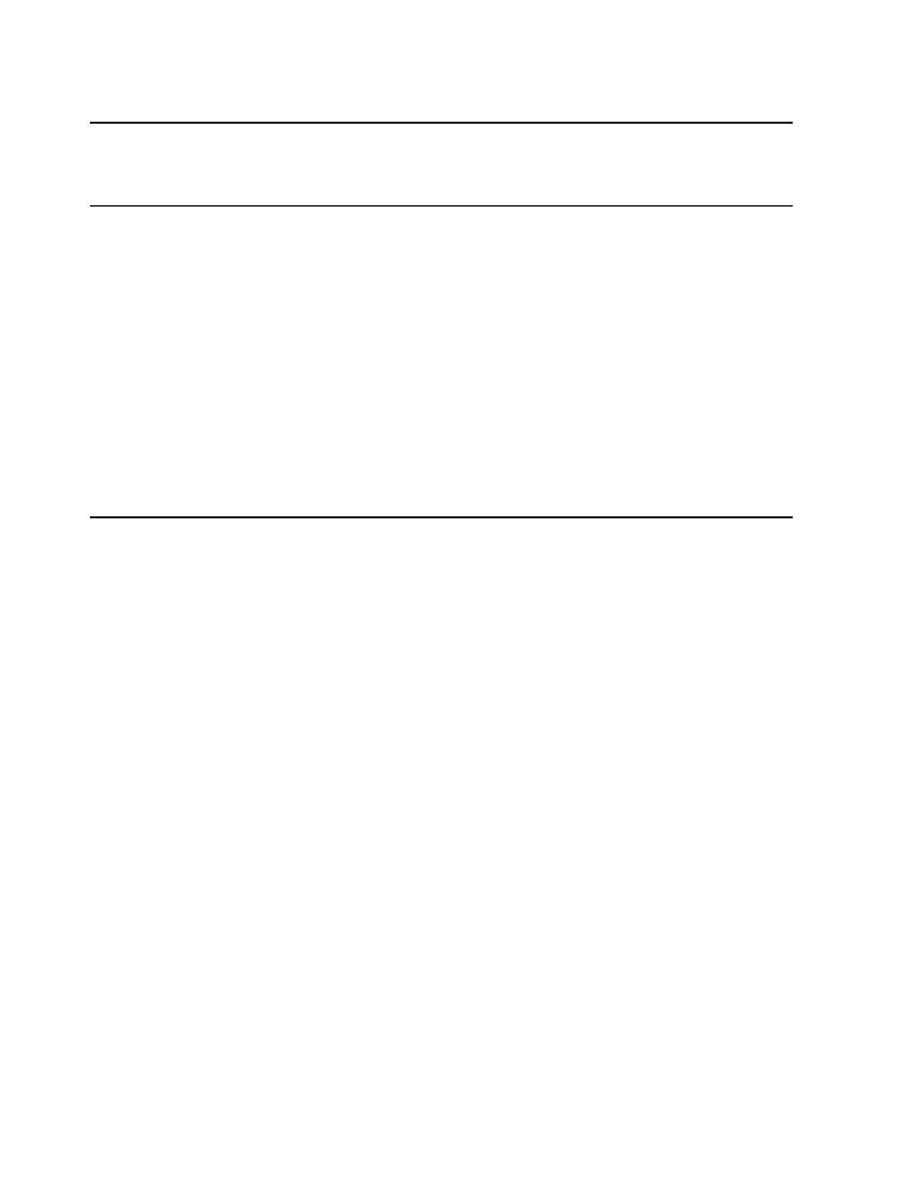

Table 4. Camp health officer comfort with skills and backup

Strongly

agree

(1)

Agree

(2)

Neither

agree nor

disagree

(3)

Disagree

(4)

Strongly

disagree

(5)

Mean

(SD)

I feel comfortable taking care of sick

or ill campers at camp

(N

123)

n

%

(95% CI)

80

65

(57%73%)

38

31

(23%39%)

4

3

(0%6%)

1

1

(0%2%)

0

0

(0%0%)

1.4

(0.6)

I have adequate medical backup if I

feel uncomfortable with a sick or in-

jured camper

(N

123)

n

%

(95% CI)

82

66

(58%75%)

36

29

(21%37%)

2

2

(0%4%)

2

2

(0%4%)

1

1

(0%2%)

1.4

(0.7)

I have a local ``camp doctor'' who is

responsive to my needs and concerns

(N

121)

n

%

(95% CI)

52

43

(34%52%)

38

32

(23%40%)

17

14

(8%20%)

9

7

(3%12%)

5

4

(1%8%)

2.0

(1.1)

I feel comfortable with my local ambu-

lance service

(N

125)

n

%

(95% CI)

62

50

(41%58%)

37

29

(22%38%)

21

17

(10%23%)

5

4

(1%7%)

0

0

(0%0%)

1.7

(0.9)

I feel comfortable with my local emer-

gency department

(N

125)

n

%

(95% CI)

57

46

(37%54%)

48

38

(30%47%)

12

10

(4%15%)

5

4

(1%7%)

3

2

(0%5%)

1.8

(0.9)

their medical backup (Table 4). In all categories, the

CHOs were confident about their own skills and about

the medical backup that they received. Most agreed or

strongly agreed with all questions. There was also no

statistical difference in the comfort score when com-

pared with the defined levels of CHO training or the type

of receiving facility (P

.05).

In the total Michigan camp population, the percentage

of camps that were categorized as rentable by the state

was 80%, while 83% of the responding camps catego-

rized themselves as rentable (z

0.713, P

.05). Sim-

ilarly, the percentage of camps that were categorized as

winterized by the state was 63%, compared to 64% in

the returned sample (z

0.231, P

.05).

Discussion

While all of the camps that responded to this survey are

in compliance with the laws of the state of Michigan,

the results raise many concerns. In many cases, CHOs

have minimal medical training and experience. They are

often placed in situations in which definitive care is a

prolonged distance away. While they are expected to

have a ``camp physician'' who has reviewed their stand-

ing orders and is their medical backup, some CHOs do

not know who their ``camp doctor'' is. Often, CHOs do

not know the training and capabilities of the local EMS

providers who respond when they call 911. In addition,

much of the medical care of campers outside camp takes

place in an acute care setting, even though primary care

coverage should have been arranged. Note also that all

of these findings occurred in one of the six states rec-

ognized by the CDC as having the best camp oversight

of any in the nation. Despite the previously mentioned

concerns, the CHOs themselves are comfortable with

their own skills and medical backup.

Only 2 of the camps responding reported having im-

mediate access to automated external defibrillators.

While the American Heart Association states that there

is insufficient evidence to recommend automated exter-

nal defibrillator use in children younger than 8 years,

their presence in camps that are quite distant from de-

finitive care should be considered.

11

Resident camps do

serve a population the majority of which is older than 8

years, and they frequently have adult visitors and staff.

To decide whether to make the investment in this tech-

nology, camps should look at the following issues: 1)

What is the level of EMS support and defibrillation

availability in their area? 2) How long would it take for

an EMS crew to arrive? and 3) Does the risk of cardiac

events in the population they serve warrant having this

technology rapidly available? Cardiopulmonary resus-

citation training should also be recommended for all

camp staff and should be required for those who super-

vise high-risk activities.

Leaving campers at a camp is an event that may create