ROBOTIC CARDIAC SURGERY

Volume 13, Number 6, 2003

461

may visualize and manipulate simulated objects in-

teractively, and once optimal access port placements

are determined, the positions of the simulated tools

can be recorded and marked directly on the patient to

specify positions for port incisions. Current research

being conducted in collaboration with Carpentier is

focusing on simulating and planning robotic proce-

dures. Surgeons will have a virtual platform to analyze

and plan optimal topographic surface targets that

would optimize port site placement. Such three-

dimensional planning systems based on preoperative

imaging data have already been introduced into other

surgical specialties, including craniomaxillofacial and

orthopedic surgery.

VI. CONCLUSION

Clearly, advances in cardiopulmonary perfusion,

intracardiac visualization, instrumentation, and ro-

botic telemanipulation have hastened a shift toward

effi

cient and safe minimally invasive cardiac surgery.

Today, cardiac surgery, particularly valve surgery done

through small incisions, has become standard practice

for many surgeons. Moreover, closed-chest coronary

bypass surgery is in its early developmental phases.

A renaissance in cardiac surgery has begun, and

robotic technology has provided benefi ts to cardiac

surgery. With improved optics and instrumentation, in-

cisions are smaller. Th

e placement of wrist-like articula-

tions at the end of the instruments moves the pivoting

action to the plane of the operative fi eld. Th

is improves

dexterity in tight spaces and allows for ambidextrous

suture placement. Sutures can be placed more accu-

rately because of tremor fi ltration and high-resolution

video magnifi cation. Furthermore, robotic systems may

serve as educational tools. In the near future, surgical

vision and training systems may be able to model most

surgical procedures through immersive technology.

Th

us, a "fl ight simulator" concept emerges where one

may be able to simulate, practice, and perform the op-

eration without a patient. Already, eff ective curricula

for training teams in robotic surgery exist.

Robotic cardiac surgery is an evolutionary pro-

cess, and even the greatest skeptics must concede that

progress has been made. Surgical scientists must con-

tinue to evaluate this technology critically in this new

era of cardiac surgery. Despite enthusiasm, caution

cannot be overemphasized. Surgeons must be careful,

because indices of operative safety, speed of recovery,

level of discomfort, procedural cost, and long-term

operative quality have yet to be defi ned. Traditional

cardiac operations still enjoy long-term success with

ever-decreasing morbidity and mortality, and thus

remain our measure for comparison.

REFERENCES

1. Stevens JH, Burdon TA, Peters WS, Siegel LC,

Pompili MF, Vierra MA, St Goar FG, Ribakove

GH, Mitchell RS, Reitz BA. Port-access coronary

artery bypass grafting: a proposed surgical method.

J Th

orac Cardiovasc Surg 1996; 111:56773.

2. Pompili MF, Stevens JH, Burdon TA, Siegel LC, Pe-

ters WS, Ribakove GH, Reitz BA. Port-access mitral

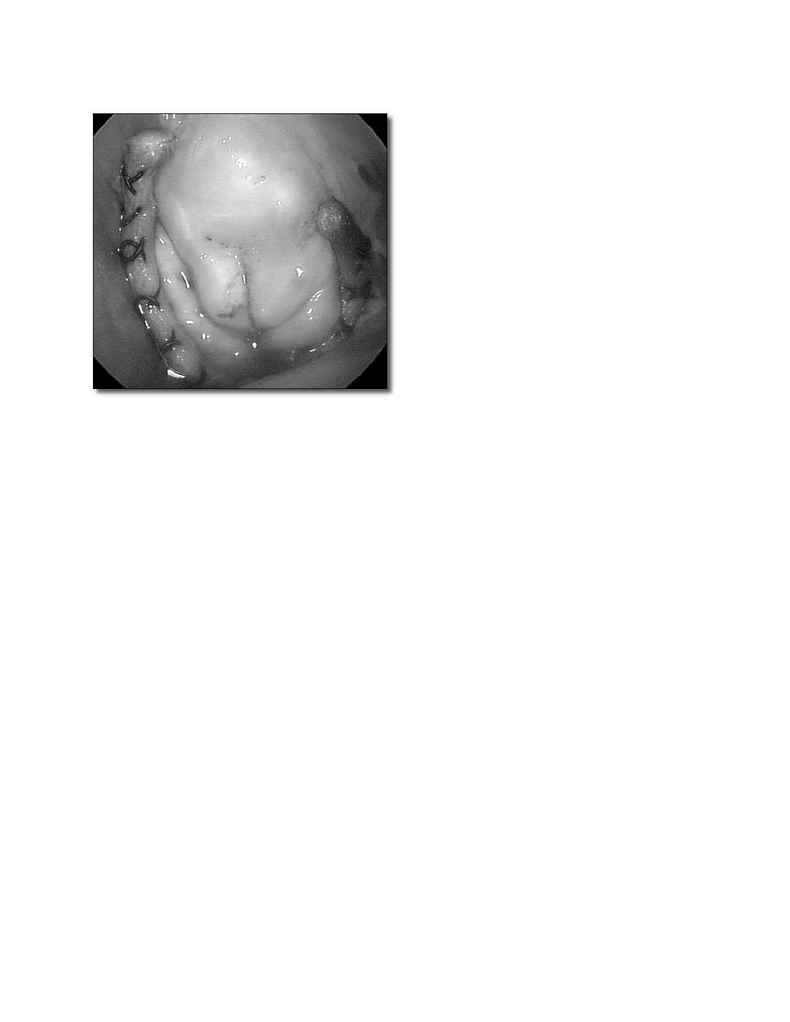

FIGURE 7. Nitinol U-clipsTM holding mitral annuloplasty

band in place.