Unit-Specific Pharmacists

Vol. 28 No. 1 · January 2003 ·

P&T

®

57

by virtue of their positive interpretation. Our presence on the

patient-care units has added a degree of security that may not

be easy to quantify, although it has been felt and greatly ap-

preciated. Our attitudes, as well as our responsibilities and ac-

countability, have changed. As time passes and growth con-

tinues, methods of data collection may be altered to absorb new

clinical plans.

We are now researching the development of a patient-safety

program devoted to cardiac anomalies to screen patients who

are taking drugs that interact with the specific cardiac indica-

tors. As we peruse the available literature, we expect to uncover

new areas that need to be addressed, thereby expanding our

services to patients and to specialties within allied health care.

The unit-specific pharmacist program, originally designed

to prevent medication errors prospectively, has had a benefi-

cial effect on the hospital's other departments and services. The

program has defined and improved our role with respect to the

nutrition-support team and to the pharmacists who accom-

pany the clinical dietitians on daily rounds as they diligently

evaluate each patient and custom-tailor their respective nutri-

tion formulas. The clinical dietitians and the pharmacists have

worked together to create an interdisciplinary "performance

improvement key process" for the past year, which has been

very educational.

We have discovered that many of our allied health staff

members are flourishing because of the improved communi-

cation from the pharmacy. In response to this benefit and

as an extension of the program, we have created "Newslet-

ter Live," an educational, quarterly seminar presented by

the director of pharmacy. Since its inception, the seminar,

which is open to all hospital staff members, has become a

well-attended and a highly anticipated event. Sessions feature

current medication information, pharmacy policy updates,

and relevant facts, extracted from our pharmaceutical journal

readings that we have compiled into an easy-to-follow outline.

This program has greatly improved communication channels

within the multidisciplinary team and has allowed a forum for

the exchange of ideas between professionals.

It was also a challenge for us to convince the pharmacy staff

of the benefits of the new program. Some pharmacists who

had originally been skeptical about the sudden role change

needed reassurance that their expertise would be necessary

on both sides of the program. With time, some staff members

became interested in participating in the program as they

grew comfortable in becoming more visible within the hos-

pital. We needed to ensure that the functions of the pharma-

cists who remained in the pharmacy complemented, but did

not impede, the development of the new system. We consid-

ered it essential that each person be incorporated into the new

plan and not be ignored or forced into a role that would fos-

ter resentment or insecurity.

SUMMARY

Our goal with the unit-specific pharmacist program was

to address the need to prevent medication errors and to use

the pharmacist's knowledge and expertise, virtually at the

patient's bedside. The benefits of the program were far

greater than we anticipated. A major benefit was an in-

creased awareness that flexibility can be incorporated into

any hospital structure by using resources that are already

in place within the multidisciplinary team.

SUGGESTED READINGS

Crane V. Critical success factors in preparing for a JCAHO survey.

Pharmacy Practice News,

February 1722, 2002.

Guharoy R. Pharmacy paradigm shift: The challenges in the new mil-

lennium. The Pharmacist May/June 69, 2001.

Johnson N. Assessing the impact of outcomes projects: Take your lead

from the AHRQ approach. Formulary 2002;37:148158.

Johnson S, Blanchard K. Who Moved My Cheese? New York: Putnam;

1998.

Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Com-

prehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals: The Official Hand-

book (CAMH).

Oakbrook Terrace, IL: 2000.

Massaro FJ. Improving a medication error monitoring program at an

acute-care hospital. Hosp Pharm 2002;37(3):259266.

McDaniel MR, DeJong DJ. Justifying pharmacy staffing by presenting

pharmacists as investments through return-on-investment anal-

ysis. Am J Health Syst Pharm 1999;56:22302234.

McWhinney BD. Reducing the Human and Economic Costs of Drug

Therapy Complications: Responding to the Medication Safety Issue

.

Dublin, OH: Cardinal Health, Inc; 1998.

Schneider PJ. Five worthy aims for pharmacy's clinical leadership to

pursue in improving medication use. Am J Health Syst Pharm

1999;56:25492552.

Weidle P, Bradley L, Gallina J, et al. Pharmaceutical care intervention

documentation program and related cost savings at a university

hospital. Hosp Pharm 1999;34(1):4352.

Zachry WM, Bootman JL. The role of the pharmacist in reducing pre-

ventable adverse drug events. P&T 2001;26(8):436440.

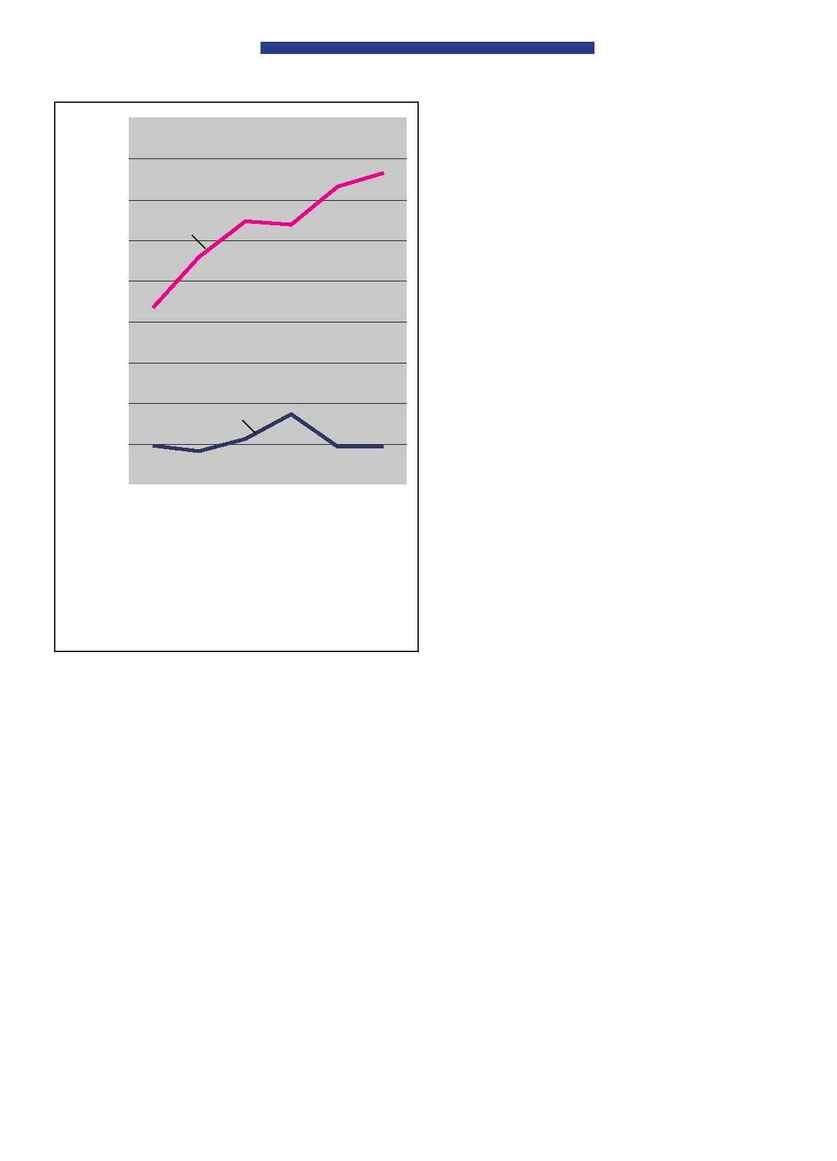

450

400

350

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

Sept.

Oct.

Nov.

Dec.

Jan.

Feb.

Number of

48

41

56

87

47

47

interventions

20002001

Number of

218

279

324

319

366

383

interventions

20012002

Figure 4 Comparison of interventions by pharmacists.

Number of interventions

20002001

Number of interventions

20012002