and by interviewing project leaders at other hospitals to learn

how to apply their successes to our institution. Through this

communication with end-users of information, we were able to

determine the degree of effectiveness at our own institution.

We addressed the challenge of improving our patient care

and pharmacy services primarily from the federal Agency for

Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) model. This agency

had developed a process of evaluating pharmaceutical out-

comes to assess the outcomes projects that it was funding. We

found this methodical tool simple enough to execute and de-

velop within the limitations of our resources, and we used it

successfully to evaluate our progress. Each "challenge" was

presented with a "plan of approach," a "data source," and an

evaluation of the "outcomes and impact of intervention." Our

goal was to seek new knowledge about clinical outcomes to in-

fluence our pharmacy practice guidelines and drug therapy pol-

icy. We believed that measuring the cost-effectiveness of phar-

maceutical interventions and evaluating changes in patient

therapies was the best way to ensure the success of our pro-

gram. Over time, we created our own model of expertise

through the routine exercise of communicating within our

multidisciplinary health care team, which then allowed every-

one involved to comprehend what we were trying to accom-

plish and how we were going to achieve it.

All of our energies focused on clinical pharmacy interven-

tions for ambiguous orders, incorrect dosing, drug interac-

tions, intravenous-to-oral conversions, and adjustments to renal

dosing. Through this practice, we continuously built upon our

efforts by identifying important factors relating to pharmacy

and patient care. Unexpected findings during the course of the

program helped us to expand our goals. Using the AHRQ

model's performance measurement table, we evaluated our

success by presenting challenges in the form of what we hoped

to accomplish. We then established an approach and simply ex-

plained how we would accomplish it.

After we executed our planned approach and gathered our

data, we evaluated the impact of our intervention to assess our

accomplishments. After evaluating the challenge, we reflected

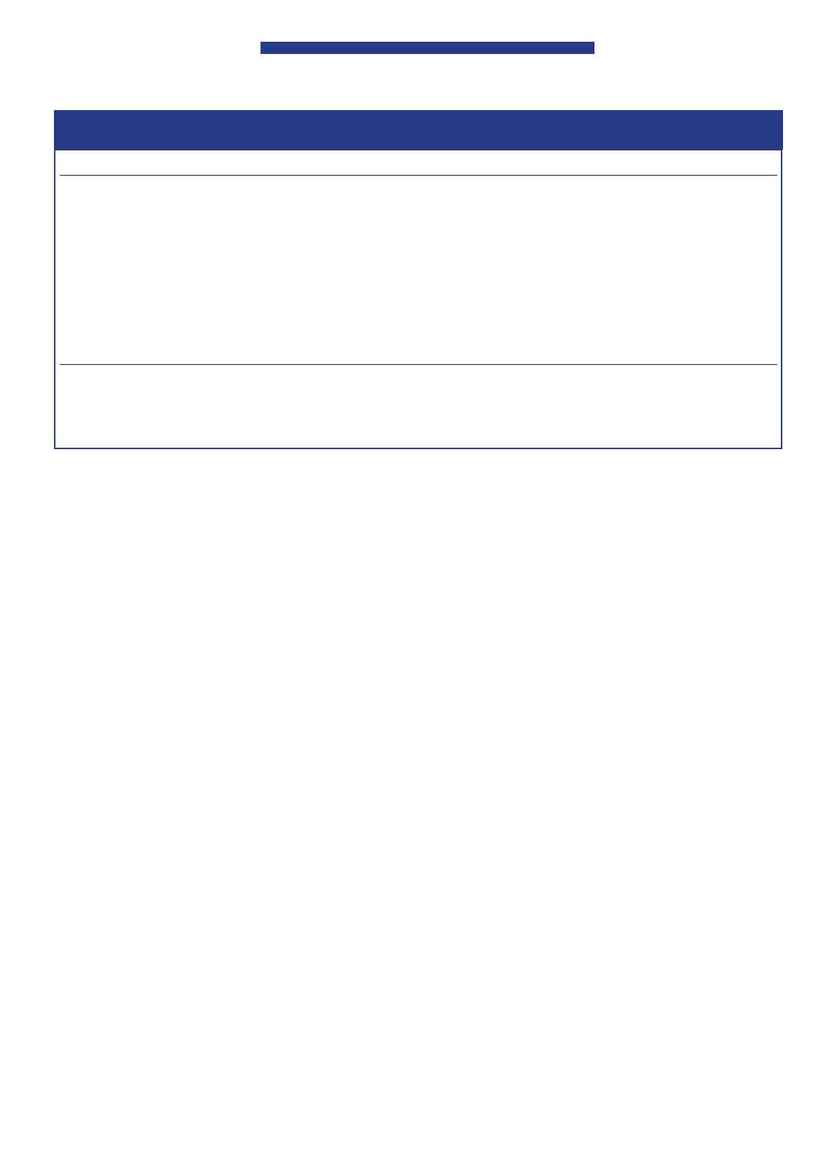

Unit-Specific Pharmacists

54 P&T

®

· January 2003 · Vol. 28 No. 1

IV Medication

Oral Medication

Renal Dosing CrCl < 40

Famotidine (Pepcid®, Merck) 20 mg q12h

Nizatidine (Axid®, Reliant) 150 mg q12h

Nizatidine 150 mg q24h

Fluconazole (Diflucan®, Pfizer) 400 mg q24h

Fluconazole 200 mg q24h

Fluconazole 200 mg q24h

Fluconazole 100 mg q24h

Gatifloxacin (Tequin®, Bristol-Myers Squibb)

Gatifloxacin 400 mg q24h

Gatifloxacin 200 mg q24h

400 mg q24h

Gatifloxacin 200 mg q24h

Gatifloxacin 200 mg q24h

Ciprofloxacin (Cipro®, Bayer) 400 mg q12h

Ciprofloxacin 500 mg q12h

Consult physician for

dose adjustment

Ciprofloxacin 200 mg q12h

Ciprofloxacin 250 mg q12h

Consult physician for

dose adjustment

Pantoprazole (Protonix®, Wyeth-Ayerst) 40 mg q24h Pantoprazole 40 mg q24h

Criteria necessary for automatic IV to PO conversion:

· Patient is taking other medications orally

· Patient has a functional gut and is eating

· Patient has been receiving the IV form for at least 48 hours

CrCl = creatinine clearance; IV = intravenous; PO = oral.

Table 1 Medications Approved for Automatic Intravenous-to-Oral Conversion

on the entire process to determine whether we could apply the

findings to other areas. Table 2 presents our actual perfor-

mance measurement.

Our collected data included the number of missing medi-

cations, dosing adjustments, intravenous-to-oral drug conver-

sions, and adverse drug reactions. The information was doc-

umented and obtained primarily via direct observation by

clinical pharmacists on a daily basis.

Our program's success has prompted the hospital's admin-

istrators to expand the clinical pharmacy program from three

nursing units to all patient-care areas with patient stays longer

than 24 hours, with a proposal to extend this period to seven

days a week. We obtain patient laboratory data directly from

our laboratory department through electronic resources in

the institution or from the patient's chart. We record the data

pertaining to all of our interventions on Microsoft Excel

®

spreadsheets once a month to present to the P&T committee,

and we confirm the accuracy and completeness of our data

when the clinical pharmacists consult with colleagues on the

multidisciplinary team. Despite the small size of our hospital,

we have developed the ability to communicate effectively with

the entire multidisciplinary team on a daily basis.

After the program became part of the daily pharmacist ros-

ter assignment and the pharmacists became familiar with the

routine, we reported our first experiences to other committees

that were also concerned with preventing medication errors.

Although the data were uniform and consistent, the emphasis

varied, depending on the focus of the committee. We notified

the administration of any problems or changes in the pro-

gram's progress.

Our report to the P&T committee during the first couple

of months of the program demonstrated a three-fold increase

in the number of interventions documented (Figure 4). This

result was considered to have a positive effect on improving

patient care, in documenting potential errors and near-misses,

and in conserving hospital resources.

The data that we have been collecting are ongoing and dy-

namic, and they clearly show changes in patient care simply