Unit-Specific Pharmacists

Vol. 28 No. 1 · January 2003 ·

P&T

®

53

was evident, and they, too, shared in the hos-

pital-wide mission to prevent medication er-

rors. The medical staff and members of the

P&T committee and the hospital's medical

board listened to our plans and accepted our

goals as presented.

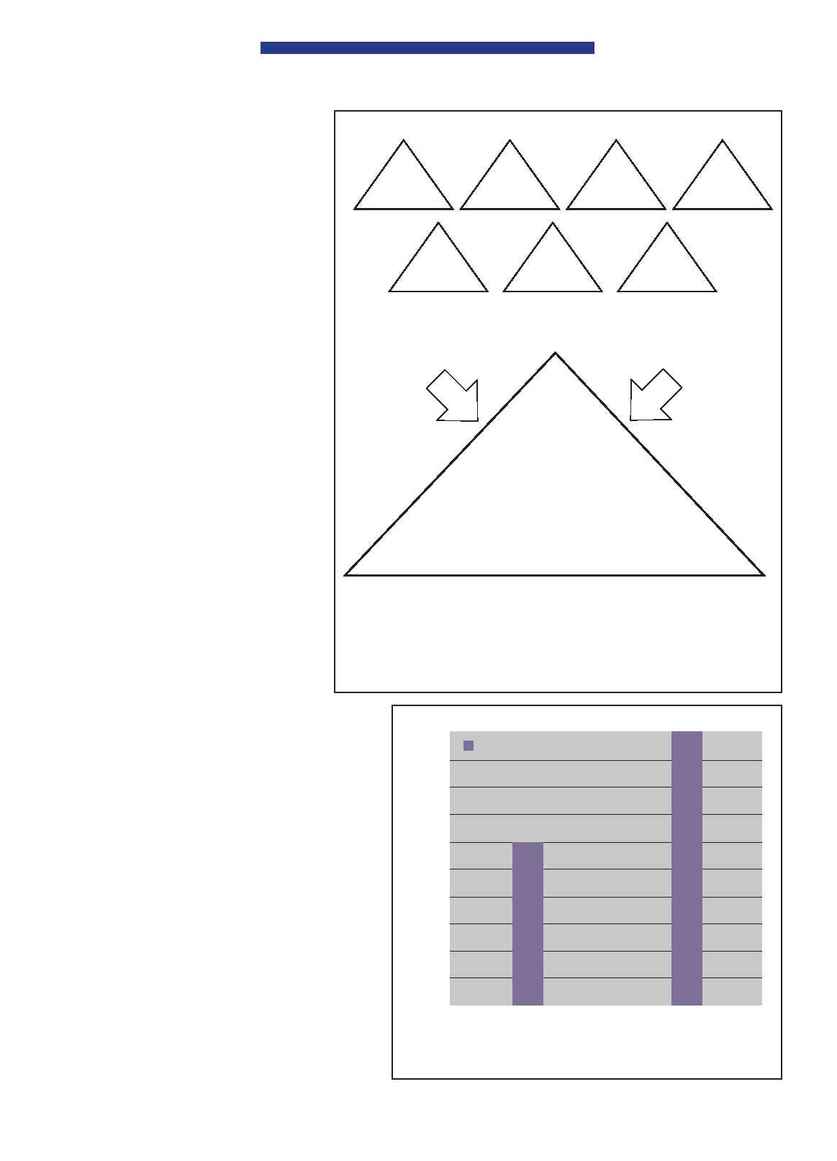

The reporting of accumulated adverse drug

reactions (Figure 3) is ongoing. All reports are

funneled to the clinical pharmacist for research

and follow-up. We have re-educated our pro-

fessional staff on the importance of docu-

menting adverse drug reactions. We promoted

error-reporting as an educational tool, which

was an integral part of the continuum of patient

care and safety. The pharmacist has thus be-

come the first line of defense in the process of

defining and documenting adverse drug reac-

tions and other intervention data.

The data accumulation for the intravenous-

to-oral conversions occurs several times per

week as the unit-specific pharmacist makes

rounds with pharmacy computer-generated

drug profiles. This allows the pharmacist to

categorize the five medications approved by

the P&T committee for automatic intravenous-

to-oral conversion (Table 1) and to identify the

patients who are receiving them. The phar-

macist can then refer to the patient's chart to

see whether the patient profiles satisfy the pre-

approved criteria, and the change can then be

noted on the chart.

Decreasing the dosage of some medications

that affect the renal system, such as nizatidine

and the quinolones, is accomplished in a sim-

ilar way. The pharmacy computer generates

profiles of drug usage to quickly highlight the

changes needed. The pharmacist then makes the nec-

essary entry into the patient's chart if the patient quali-

fies for a change in drug dosing.

REPORTING OF OUTCOMES

In a hospital environment, performance measurement

and its proper organization and communication are cru-

cial to any new performance improvement initiative. Our

pharmacist intervention indicators were changed to re-

flect those areas that our clinical pharmacists consid-

ered to be problematic; interestingly enough, these areas

had not been noticed before but they arose from obser-

vations and early experiences on the patient-care units.

Pharmacy intervention indicators are opportunities for

pharmacists to intervene, in a timely fashion, in pre-

scribed ordering and patient care. These indicators in-

clude allergies, order legibility, drug interactions, dose

adjustments, drug information, dosages, frequency and

usage of medication, missing medications, nonformu-

lary drug requests, and switches from intravenous to

oral medications.

We first identified useful methodologies for conduct-

ing outcomes assessments by reviewing the literature

Allergies

Dose

Frequency

Usage

Drug

Information

Interactions

Incompatibility

Order

Clarification

Nonformulary

Drug requests

Allergies

Order legibility

Drug interactions

Renal adjustment

Drug information

Dosagefrequencyusage

Missing medications

Nonformulary drug requests

IV to PO medication changes

IV

Solutions

Unit-Specific Pharmacist Program

Figure 2

Evolution of intervention indicators. As the unit-specific pharmacist

program evolved, the opportunity to intervene became more apparent because

the pharmacist could focus entirely on pharmaceutical care as a part of the

multidisciplinary team.

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

March 2000 to

February 2001

Adverse drug reactions

60

March 2001 to

February 2002

Number of reports

100

Figure 3 Reports of adverse drug reactions.